Amongst What’s Fallen / A Tree On A Hill

For Electronics, Dancers and Musicians

Premiered at the RAMBERT School of Contemporary Dance, London (2025)

in collaboration with Margarida Gonçalves, Salvador Sanches and dancers from RAMBERT School of Contemporary Dance

Our work, Amongst What’s Fallen for four dancers, three musicians and electronics, was inspired by the idea of the struggle of nature within an urban setting. Both the music and choreography deal with a push-pull between natural movement and rigidity, showcasing forces of nature around stubborn industrial efforts. Starting with the idea of breath as the central axis of nature, we grew ideas from this point in an unfolding manner, gradually pulling nature into industry and chaos, until it moves back into itself. We slowly crowded the breath with sounds and movements of modernism and technology, until it loses itself but not completely.

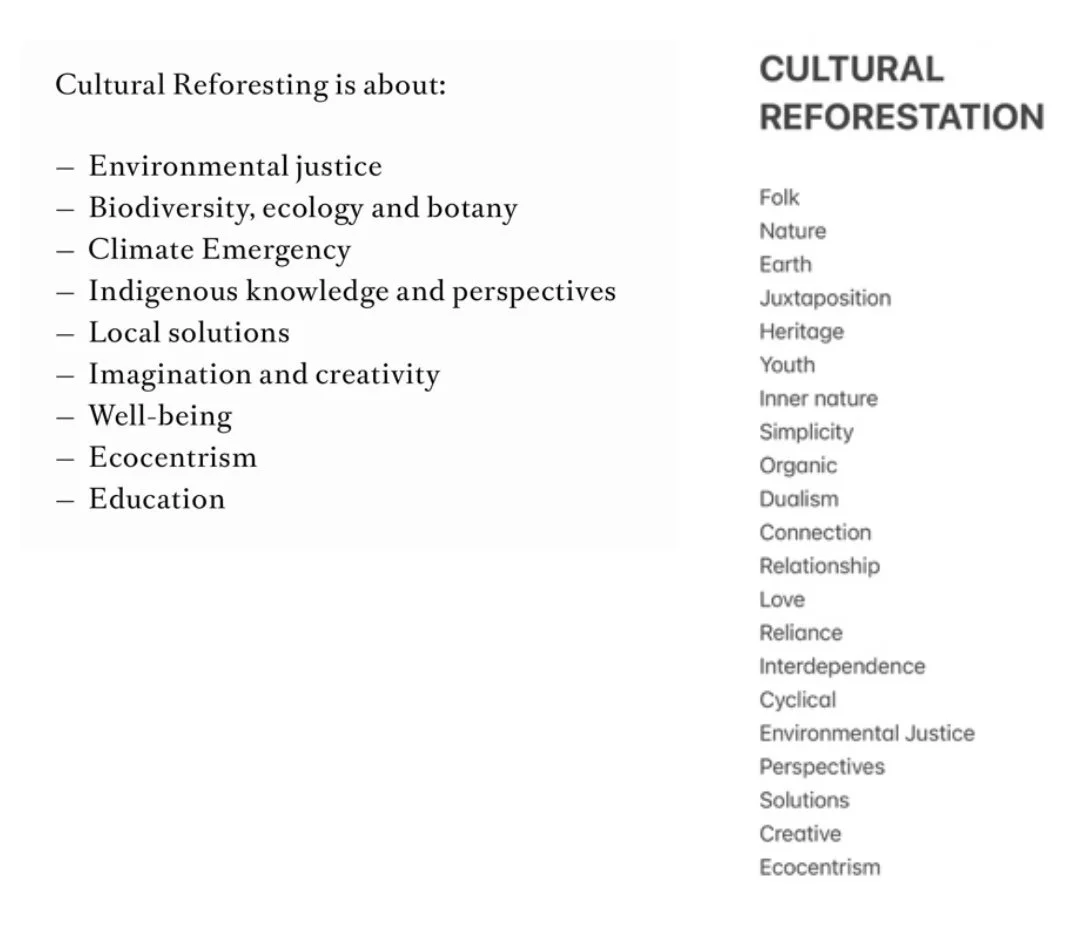

The ideas began with discussion, sharing materials from Anna Theresa De Keersmaeker and Thierry De Mey’s Rosas danst Rosas (1997), to Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988), and Crystal Pite’s Assembly Hall (2023) and Light of Passage (2022). We also shared our own works, finding a shared interest between everyone. Together, we combined these materials to create a list of vocabulary around ‘Cultural Reforestation’:

Figure 1: Detail from a group folder of materials

The music grew from breath, into a recording of the words of J. Krishnamurti from his Conversations with Allan W. Anderson: 8, Does pleasure bring happiness? 5 Krishnamurti was a spiritual teacher who spent his life traveling across the world, trying to convey energy with words. Throughout the Conversations, Krishnamurti talks through the meaning of life, our purpose and responsibility on this earth. He speaks about death, love, pleasure, fear and joy, all witnessed from a single point called meditation. In Amongst What’s Fallen I sampled the moment when Krishnamurti encourages us to remove thought from our minds completely, so that we can enjoy nature and the world around us every day. The piece was based around the idea of paying attention to, appreciating and being ‘one’ with nature, as that is who we are at the core.

Figure 2 Still image from Krishnamurti's Conversations with Allan W. Anderson: 8, Does pleasure bring happiness?

We all agreed to work with electronic music, using speech to narrate the work. Initially, I would fold and abstract the voice using time stretching, reversing and cutting. However, Krishnamurti’s speech was so captivating, I decided to share his message as it was intended. Separately, I composed the music for the piece, recording my voice and sampling Krishnamurti. For me, to bring valuable work to the group, I needed time in solitude, to create ‘deep work’. ‘Deep’ as Pauline writes in Deep Listening (2005), is “to do with complexity and boundaries, or edges beyond ordinary or habitual understandings… A subject that is “too deep” surpasses one’s present understanding or has too many unknown parts to grasp easily.” To create deep work, I needed to break away from the external conversations and move into a space or silence with myself. The duality of inner work, versus group work seemed to be of one entity. From experience, if the music feels authentic to me, and moves me, I know it will for someone else. Although everybody is an individual, each human has the same fundamental needs and emotions. Therefore, it was important for me to write the initial music in solitude, reflecting on how my life experiences could resonate with the wider group and audience. My role was towrite a personal composition, that would a ripple outward onto the choreography, dancers and other musicians.

In an early rehearsal, Salva layered one of my vocal pieces with David Lynch’s Industrial Soundscape (2002), creating a steady but impactful beat for the dancers. The rhythm fit perfectly with the aesthetic of the ambient piece, and together we worked on developing this beat-making technique and rhythm pattern. Margarida was also instrumental in this rehearsal, making important suggestions about the length of the vocal track and breathwork, expressing to leave more space and elongate the breathing. Both the beat and breath became an essential part to the music and the performance, something that I may not have considered by myself. From this point, we worked together to improve the production quality and began to weave the music into choreography and staging. The dancers combined pedestrian and natural movements, blending free improvisations with the static movements of industry. The movements became more energetic as the piece progressed, moving away from improvisation, into a choreographed and fixed set of movement, reflecting their togetherness as nature against this urban setting. Margarida and I broke away from the group, reflecting the decay and separation of nature within the modern world.

Figure 3: Image of natural movement.

Figure 4: Salva brushing leaves with a broom.

Figure 5: Image of rigid movement.

The collaborative element of the group was a great learning experience. The musicians often communicated ideas with thought, planning, words and discussion, whereas the dancers communicated via a different form of communication - movement. I observed that the dancers needed time to listen, feel and spontaneously move to the pulse and rhythm. It seemed, in order to flow with the music, dancers needed to be free of thought. The more we as musicians tried to discuss, the more agitated the dancers would become, and the more the dancers wanted to move, the more agitated the musicians became, (which became a humorous metaphor for the piece itself). As Twyla Tharp writes in The Collaborative Habit, “Collaboration guarantees change because it makes us accommodate the reality of our partners—and accept all the ways they’re not like us. And those differences are important”.

In conclusion, I learnt about the value of observation and trust. The project has helped me to expand my practice outside of solitude, allowing others to change and add to the music I write. I’ve learnt to communicate with other means and remove the critical mind from the creative process. Most importantly, Amongst What’s Fallen, gave me resilience to keep moving through a project, no matter how challenging, and trust that the process will unfold into something impactful.